Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Last Updated on: 11th March 2025, 05:09 pm

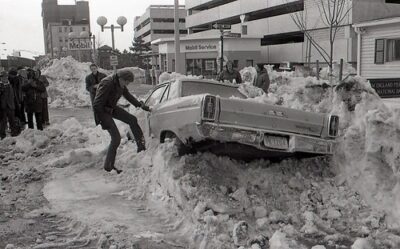

The blizzard of 1978 was fierce in New England. As an undergraduate at the University of Connecticut, it was a time for my roommates and me to stuff our bodies into as many layers of clothing as we owned, borrow a toboggan, and plod up the road to the liquor store for a case of beer. We played Monopoly for three days while the roads were closed in a state of emergency. We didn’t know then that the blizzard would be famous, nor that winter and others we had experienced would someday be described as colder and snowier than future generations would ever know.

Remember grabbing our miniature snow shovels when we were tikes and building snow forts? Oh, they were so icy cold when we proudly sat inside our creations. Remember making snow angels in the snow? Of skiing with days on end of fresh powder? Of playing ice hockey on frozen local ponds? One of the dads would check the ice safety first by standing in the middle of the shiny blue-white surface and jumping up and down, up and down.

“We are seeing an increase in daily heat records, and we are NOT seeing an increase in daily cold records,” explains Michael Mann, a climate scientist at Penn State University and good friend to CleanTechnica. He’s renowned for creating the iconic “hockey stick” graph 25 years ago that illustrates the dramatic upward trend in average global temperatures we can expect if we continue pouring enormous amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

For the fifth year in a row, late spring (April–June) snow cover extent in 2022 was smaller than the 1981-2020 average. Late spring snow cover extent has been above average just five times in the past 25 years. Yes, winters were colder and snowier when we were kids.

Wait! Haven’t New Englanders been celebrating renewed snow sports and ground blanketed by white this year? Sure, this more classic New England winter was the result of a weak La Niña weather pattern that drew in more cold air and helped to inspire snowstorms. Then again, New England winters are now three degrees warmer, on average, than they were during the Baby Boom of the late 1940s through the early 1960s, a Boston Globe analysis of weather data found.

Air temperatures on Earth have been rising since the Industrial Revolution. While natural variability plays some part, the huge body of evidence indicates that human activities — particularly emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases — are mostly responsible for making our planet warmer. The global temperature mainly depends on how much energy the planet receives from the Sun and how much it radiates back into space. The energy coming from the Sun fluctuates very little by year, while the amount of energy radiated by Earth is closely tied to the chemical composition of the atmosphere — particularly the amount of heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

The globe’s 21st-century heating becomes all the more stark when compared to the coldest years on record. The planet’s 20 coldest years all occurred nearly a century ago, between 1884 and 1929. About one-third of Earth’s land surface is covered by snow for some part of the year. The bright white covering affects global conditions by reflecting solar energy away from surfaces that would otherwise absorb it. NOAA says the rate of spring snow decline has been as dramatic as the rate of Arctic ice loss.

That’s important because how long the ground remains snow covered in spring affects the length of the growing season, the timing and amount of river runoff, permafrost thawing, wildlife, and fire risk. Therefore, the earlier decrease in snow cover increases the amount of sunlight absorbed by Earth, and in turn, surface temperatures.

From 1970 to 2024, average winter temperatures rose in 235 out of 241 locations in the US by an average of 4 degrees Fahrenheit. That means cold snaps, on average, are becoming shorter. And the number of days with temperatures below 32 degrees Fahrenheit has declined, and is expected to continue to drop across the country.

At regional and local scales, water resource managers, flood forecasters, and farmers are intensely interested in knowing how much water is in snow and when it will melt. Locally, snow provides moisture to soil and plants. On a larger scale, runoff from melting snow feeds streams and rivers that supply water for agriculture and cities. Knowing when and how quickly snow will turn to water is essential for forecasting if water from snowmelt will soak into the ground or cause flooding. In managed watersheds, earlier melting of snow can change when and how much water is available for various uses.

Global warming does not mean temperatures rise everywhere at every time by the same rate. So while the average amount of snow is declining in many areas of the US, the amount of snow that falls during intense snowstorms could increase in certain locations.

Temperatures might rise five degrees in one region and drop two degrees in another. For instance, exceptionally cold winters in one place might be balanced by extremely warm winters in another part of the world. Generally, warming is greater over land than over the oceans because water is slower to absorb and release heat. These temperature range analyses come from NASA, which incorporate surface temperature measurements from more than 20,000 weather stations, ship- and buoy-based observations of sea surface temperatures, and temperature measurements from Antarctic research stations. These in situ measurements are analyzed using an algorithm that considers the varied spacing of temperature stations around the globe and urban heat island effects.

Overall, a warming atmosphere means more evaporation from both land and sea, so there’s more moisture in the air – 4% more moisture per degree Fahrenheit rise in temperature. That leads to extremes. Hotter, drier areas tend to get even drier and have less rainfall, since the evaporated moisture rarely meets the colder temps that turn water vapor into liquid. In areas that do get precipitation, they get more of it: more rain (and flooding) when temps are above freezing, and when temperatures (less frequently) drop below freezing, there’s a greater chance of snowstorms that break records.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy