Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Last Updated on: 23rd March 2025, 11:34 am

Lowest Cost Buffer Matches Vehicle Charge Rate,

Charging Station Peak Power is a Cost Factor

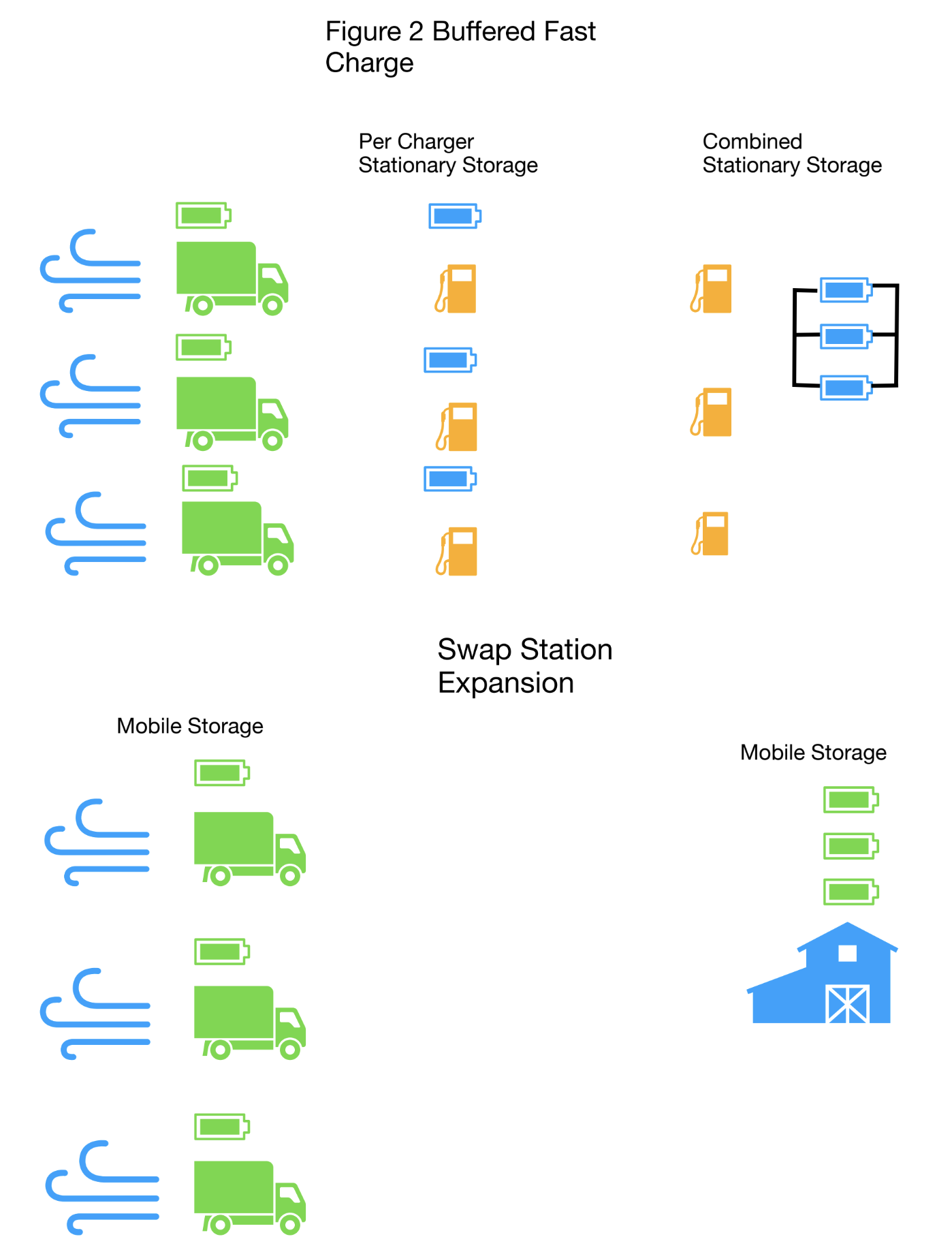

In “Why Slow Charged Swap is Better Than Buffered Fast Charge,” a detailed comparison was made of a unit transaction, which returns vehicles to a ready state for continuing transport. In this comparison, the total number of battery packs, both stationary packs at the charging station and mobile packs in vehicles, is assessed.

For swap stations, stored swap packs can buffer peak demand. For the buffered fast charge station, additional stationary packs buffer peak demand. Storage buffers are used to reduce peak demand at DC fast charge stations, as these can use upwards of 150 kW to charge vehicle packs in under an hour.

At car fast charging stations, the combined power of many charging stalls can exceed 10 MW, causing peak demand to incur excess demand charges. The utility may also pass on costs needed to upgrade distribution equipment, including substations, which can cost $4 million for 10 MVA, and peak demand charges set a profitability limit to fast charge beyond 150 kW.

Peak power is expensive. Fast charge stations now charge as much as $0.50/kWh. In order to avoid excess demand charges and utility equipment upgrade costs, battery storage buffers are now used at large fast charge stations with as many as 96 (or maybe now more) charging stalls.

Storage buffers are used for truck charging. Tesla uses Megapacks at its Megacharger stations. The storage buffers charge slowly at lower power over a longer period, and then discharge to provide peak power to customers as required.

Peak Demand Reduction Works The Same Way for Swap & Fast Charge

To reduce peak power, batteries are charged slowly, then power is drawn from storage rather than directly from the grid. The amount of power, energy stored, and time to charge is a function of the buffer and the required energy delivery amount and speed. Scenarios of overflow demand produce similar results for any station of the same capacity. The response to overflow may be a station expansion. The figure of merit for any station is the peak utility demand reduction and the level of service provided. On that basis, required capital costs, battery pack amounts, and all other factors can be considered.

Stored packs in unison can achieve the same buffer electrical performance as a single larger buffer. A large fast charge station with multiple charging stalls can be compared to a swap station with multiple packs delivering the same service. The goal is to understand and compare different methods for the same delivered service.

Slow Charged Swap and Buffered Fast Charge Scaling

For scaling purposes, fast charge stations may add additional charger stalls, and swap stations can either add more packs and faster swap mechanisms, or they can add more swap stations.

For the purposes of analyzing the peak vehicle handling capability of stations, one vehicle at one charger or one swap station with one pack can scale to meet the requirements for more service. An entire station can be treated as a single unit transaction of N vehicles, and a charge station of N charging stalls, or a swap station with N packs. By doing this, scaling reveals the results for cases.

Swap speed scales independent of electrical performance. Swap stations can expand swap speed in several different ways. Stations may be added in parallel. A swap station could also add additional lanes and lifting machines, or can increase mechanical speed.

Fast charging stalls can be added for each simultaneous request desired, and swap stations can add more packs, one per vehicle served. Multiple packs added to a swap station are connected to the grid. With N cars served, there can be N packs in a swap station, while fast charge can add a storage buffer N times the energy storage of the number of cars it serves. Likewise, any charging method can add storage buffering beyond the minimum required, with equal amounts added having similar effects. A swap station already has buffers in the station, the swap packs. Buffered fast charge adds them. In total, at initial setup, the number of packs is equal.

Mobile Packs & Transport Miles

For swap, all battery packs contribute to mobile miles. Long term, mobile miles are proportional to packs used for transport.

Stationary storage provides no mobile miles. Swap uses no fixed stationary storage, just packs that are later put back on board. The buffered fast charger method must always consume some amount of excess stationary storage buffer that does not get used for mobile transport. Buffered fast charge has greater pack costs because it requires more packs initially due to lower efficiency, and long term because swap only replaces mobile packs while buffered fast charge must replace both buffer packs and mobile packs.

Buffered fast charge first charges the buffer slowly, and then the buffer fast charges the mobile pack. For swap, no pack must ever fast charge. The sum of fast charge losses for buffer and mobile pack is a 20%.

Why Optimum Storage Buffer Design Uses Mobile Pack Chemistry

In the prior comparison, all packs are the same type, and a unit size. There is no loss of generality in results, because for optimum cost, buffer storage must be of the same characteristic as the mobile pack. It must deliver both the power and the energy required. Power means the rate energy is transferred. To analyze this, the relationships between charge rate, duration, energy capacity, pack internal resistance, and cost must be understood. Batteries have fixed power/energy ratios for a given cell.

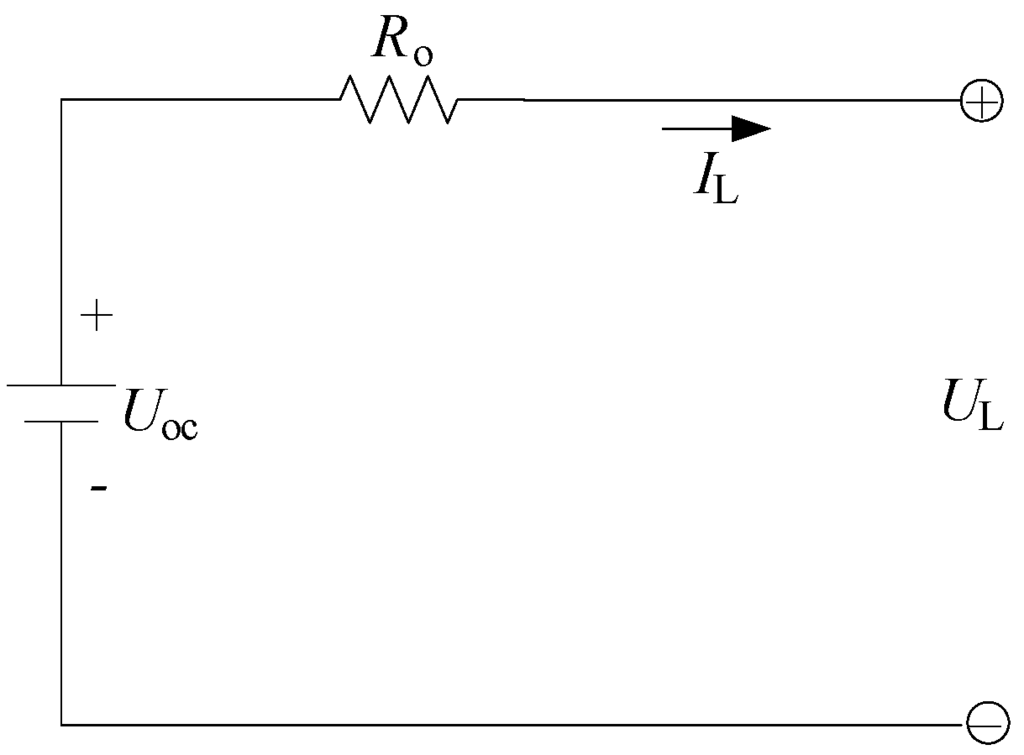

A battery cell has a simplified equivalent circuit, consisting of a voltage source in series with a resistance, referred to as internal resistance.

The amount of current delivered at a voltage is limited by the resistance. Charge rate is linked to this concept. If a battery has high series resistance, its charge rate will be lower than a battery with lower series resistance.

In particular, battery series resistance is affected by the thickness of the anode and cathode active materials. Additional active material may be used to increase the energy storage, or energy density, because more of the battery consists of active material than one with thinner electrodes. However, thicker electrodes bring the downside of increased resistance. Series resistance limits charge rate, C.

While it may be tempting to assume that batteries can just run parallel to lower equivalent resistance to increase C, that does not happen. Charge rate, or C, is a time-based property independent of how the cells are connected. No matter how they are connected, the maximum charge rate of a pack is the same as the cells used in the pack.

Battery Power Determined by Charge Rate, Duration

Charge rate sets the power/energy ratio of a battery. Battery performance is given in amp-hours. Charge rate and duration are inversely related.

Duration is the time required to completely charge or discharge a battery. When a battery has a duration of one hour, the amp-hour (Ah) rating combined with the voltage gives the same numerical power and energy, because hours is equal to one. When a battery has long duration, power and energy are not numerically equal. A one-Ah one-volt battery has one watt and one watt-hour capacity. A battery with a duration of ten hours has one-tenth the power, but the same energy. The higher the duration, the lower the power.

The power/energy ratio of a battery is:

P/E = C = 1/(duration)

Vbatt x Amp-hours = Energy, E

P = E x C

where P is Power, E is energy, Vbatt is battery voltage, and C is charge rate.

A given battery chemistry can be made to have a range of charge rates or durations by increasing electrode thickness. Thick electrodes give high energy density and high series resistance. Often, batteries are made to have low energy cost by using thick electrodes with more active material. With more active material, more energy is delivered per cell.

Lower-energy-cost batteries with thick electrodes have higher internal resistance, lower charge rates, and longer duration.

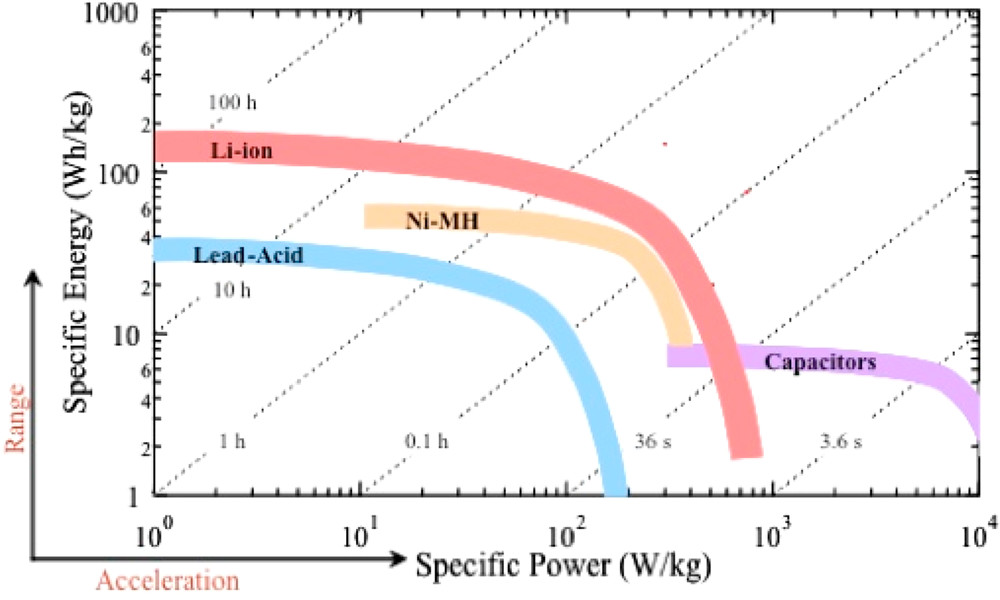

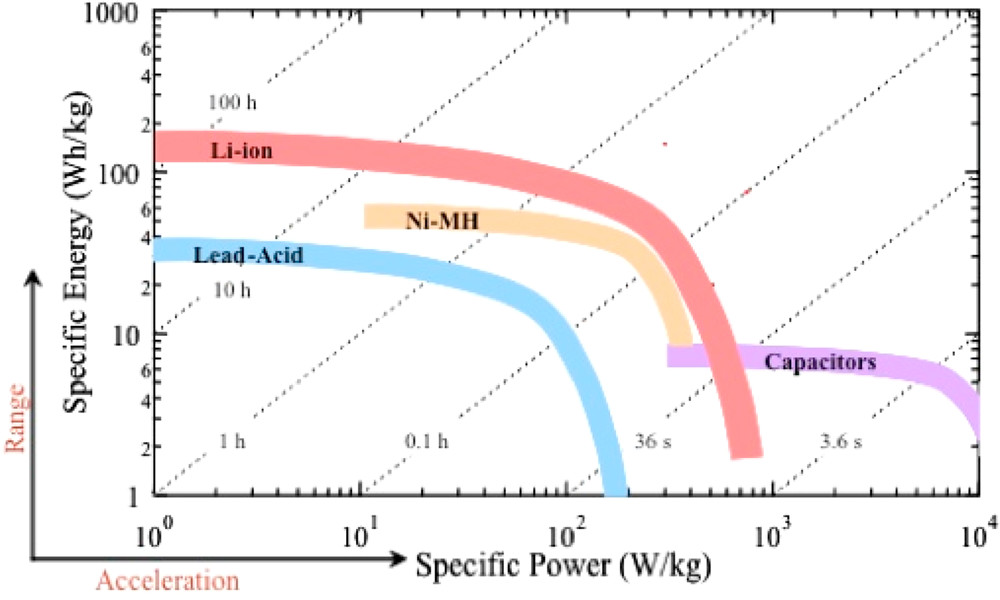

The opposite is true of chemistries with high charge rates, like lithium titanate. When resistance is low, charge rate is high. For any given chemistry, a plot of power and energy can be made showing a continuous line for a range of charge rates.

On a Chemistry Power Energy Plot, we can see a line for lead acid batteries, NiMH batteries, lithium batteries, and so on. Those curves demonstrate how changing those chemistry characteristics with thickness can vary their power/energy ratio or charge rate.

Matching Mobile Pack Produces Lowest Capital Cost

For a given chemistry type, the optimum buffer battery to charge another battery is one of the same type and characteristics. There are two causes.

First, a low charge rate pack yields a lower energy cost, but does not deliver the required power for the same energy.

Because charge rate fixes the power/energy ratio, a lower energy battery lacks power and must be sized to higher energy to deliver the power required for fast charge. This results in higher capital cost.

While the resulting larger energy capacity buffer will store more charge than required, it loses the benefit of minimum capital cost. The cost benefits are lost. The mathematics of that is shown in the article “How Can I Use A Low C Rate Battery To Charge A High C Rate Battery?”

Second, increasing electrode thickness increases energy density with a saturation effect of diminishing returns. Charge rate is not a constant when electrodes are made thicker, but falls. Cells optimized for lowest energy costs sacrifice power for energy at more than an equal rate.

As seen in the figure below from a USDOE report:

Increasing duration comes at the cost of a worse charge rate.

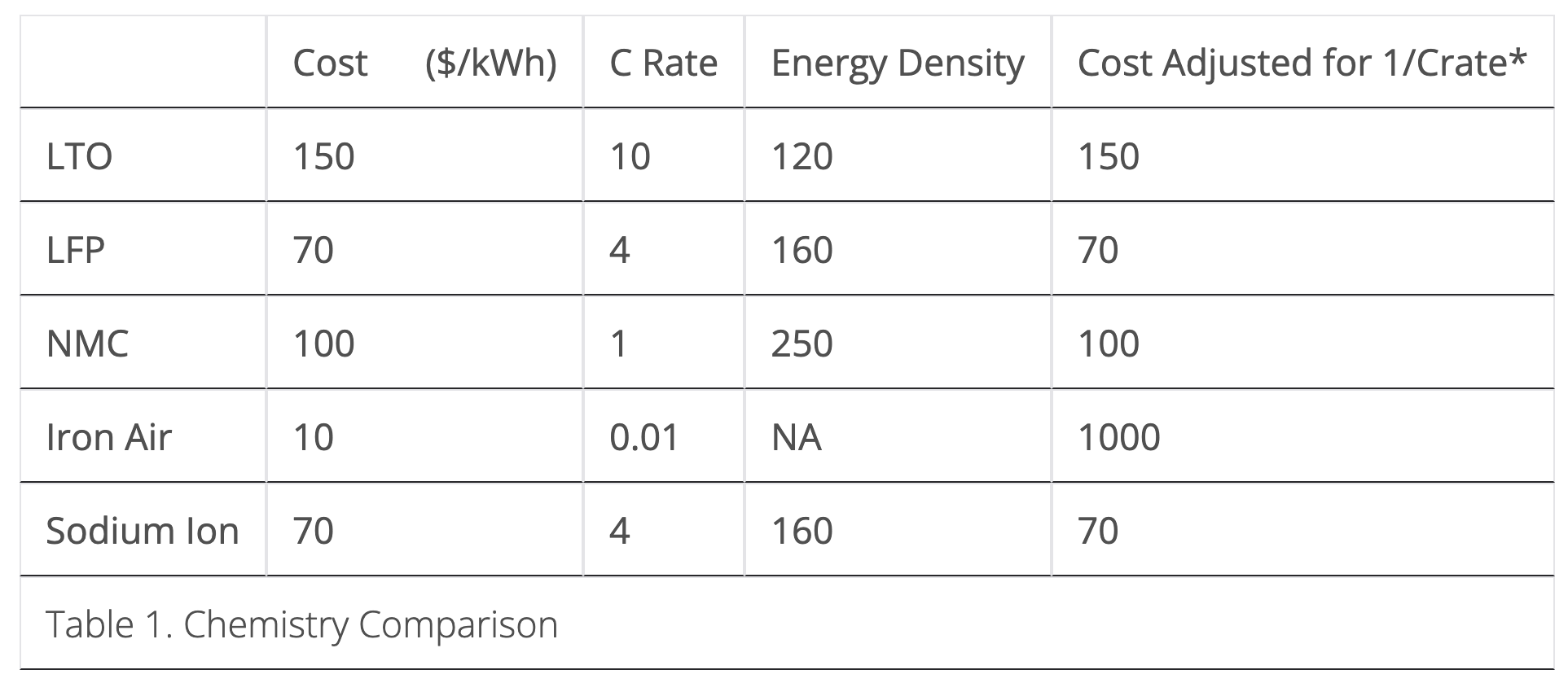

Here is an example: Recently, it was reported that an iron-air battery chemistry could outperform lithium-ion batteries with cost that is one-tenth as much. It also has a duration of 100 hours. In order to make a charge station buffer battery from an iron-air battery, it would have to be the equivalent energy capacity of 100 times a battery with a C rate of 1. A C rate of 1 is about what a typical long-range NMC EV battery is capable of. From this calculation, it can be concluded that in this application, an iron-air battery sized to meet the requirement would cost 10x what a lithium battery of the same matching type with the same C rate would cost.

Mixing Grid Power & Stored Energy

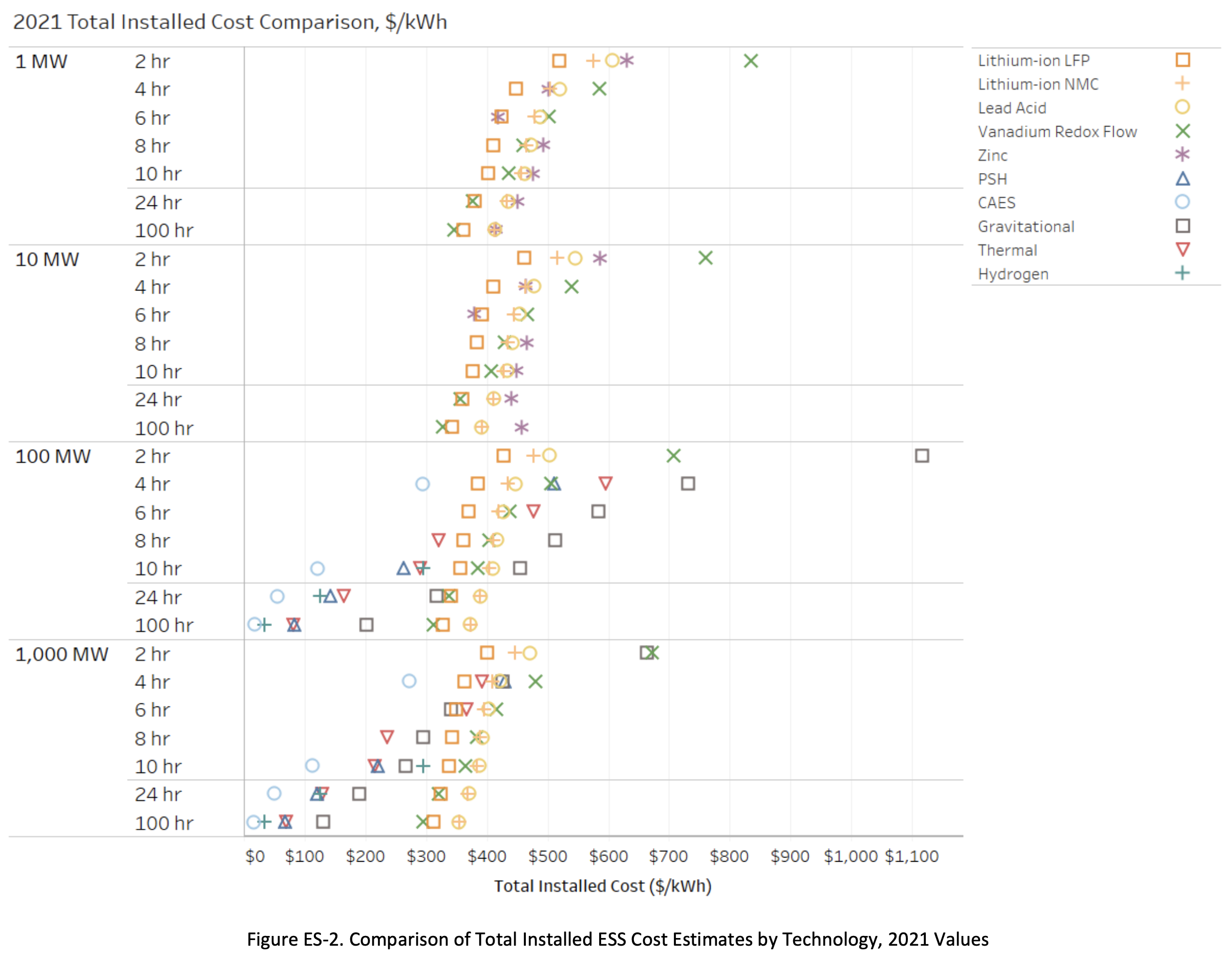

A mix of grid power and stored energy results in a blend of costs for excess stationary storage and utility peak demand costs. Peak demand charges, utility upgrade costs, and energy storage buffer costs are in the same realm. Blending grid and stored energy does not result in effective cost reduction. Buffers do not effectively reduce fast charging costs, they shift the cost from peak demand charges and utility upgrade costs to buffer costs.

Given that the cost of a substation is $4 million for a 10 MVA substation and the cost of one-hour energy storage is in the range of $100/kWh, battery only, the costs of storage is in the range of 10 MW x 1,000 kW/MW x 1 hour x $100/kWh = $1 million per MWh.

The cost of four hours of storage is similar to the cost of a substation upgrade. If the stationary storage needs to be sized larger for its low P/E ratio, it could easily cost more than the cost of a 10 MVA substation.

A Word on Equivalent Service

Fast charge introduces added latency to operations. In the time a number of vehicles fast charge simultaneously, swap vehicles are already on their way to the next station. In order to deliver the same service over time, a swap station may reduce its number of packs. For the same service as buffered fast charge, swap packs per vehicle is less than one.

Why Matching Mobile Packs is Optimal For All Chemistries

For existing chemistries, there is no lower cost buffer type than mobile packs when energy capacity is adjusted to meet the power required.

In general, for any chemistry type, on a plot of energy and power density, there is a continuous plot line with end points of higher power or energy, as seen here again:

As battery chemistry advances, better batteries have different plot lines further in the direction of the advancing y=x line, but on each plot line, the optimal P/E ratio exists for this application at the same charge rate as a mobile pack. If future battery chemistries introduce a cheaper pack for energy density with thick electrodes, the chemistry might also be used to make a lower-cost battery with higher C rate and thin electrodes for mobile use as well. The nonlinear relationship between C rate and energy density will fix an optimum point along the curve. In this manner, the relationships between power and energy will render the same optimum cost function for charging future chemistries as well.

Conclusion

The relationship showing optimum lowest cost for charge station buffer operation is achieved at matching C rate to the mobile pack for now and for any future chemistry because it is a property of cell physics and governed by charge rate mathematics.

Matching buffer packs to mobile packs creates the optimum conditions of lowest cost for buffered fast charging.

Swap uses less battery packs both initially and long term compared to buffered fast charge for the same level of service. The capital costs of battery packs is thus greater for buffered fast charge compared to swap with equal service.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy