Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Industrial heat has always been the awkward uncle at the decarbonization dinner table. Loud, a bit old-fashioned, and responsible for about 20% of global carbon emissions, but nobody really wants to talk about him. The climate conversation has been dominated by glitzier topics like electric vehicles and green hydrogen, the latter mostly to the detriment of real decarbonization.

Meanwhile, the reality is that roughly two-thirds of industrial energy demand goes toward heat, and about 40% of that heat sits in the 100° to 200° Celsius range. That’s not steelmaking heat. It’s not glass or cement. It’s the everyday kind of heat that dries paper, pasteurizes milk, cooks chemicals, and cures paint. We burn an awful lot of gas and coal to make it. Globally, that heat is responsible for somewhere north of 10 gigatonnes of CO₂ per year. That’s not a rounding error.

As a note, this is one in a series of articles on geothermal. The scope of the series is outlined in the introductory piece. If your interest area or concern isn’t reflected in the introductory piece, please leave a comment.

The good news is we already have the tools to fix it — at least the low-to-mid-temperature part of it. This is not a story about experimental supercritical wells or AI-controlled concentrating solar mirrors. It’s about using 80° to 120° Celsius geothermal heat — conventional stuff, no fracking or absurd depths — and combining it with industrial heat pumps that are finally stepping out of their utility-room shadow and into real factory floors. The idea is simple. Drill a moderately deep hole, pull up water that’s already hot enough to be useful, then use a heat pump to boost it to the final temperature needed for the process, whether that’s 120°, 140°, or even 180° Celsius. Geothermal heat becomes the base and the heat pump is the supercharger.

This isn’t just theory. In Kawerau, New Zealand, a pulp and paper mill recently converted one of its tissue machines to run entirely on geothermal steam, cutting site emissions by 25%. The geothermal field nearby provides 200° steam, piped directly to the plant, and the entire operation functions with no combustion. No flue gas, no carbon pricing headaches, no fuel trucks. It’s an actual operating facility producing commercial volumes of tissue paper.

In Neustadt-Glewe, Germany, a town has been using a 98° geothermal well for district heating since the 1990s. Recently, they added a 1.4 megawatt thermal ammonia heat pump, which extracts more value from the same well, boosting water temperature and increasing output by 30%. That’s with a COP of about 3.8, which, for context, means every kilowatt-hour of electricity delivers nearly four kilowatt-hours of heat.

The levelized cost of heat (LCOH) for a well-optimized geothermal plus heat pump system ranges between US$20 and $60 per megawatt-hour, depending on local drilling costs and electricity prices. In contrast, gas boilers, even before factoring in carbon costs, typically deliver heat at $30 to $45 per megawatt-hour at current gas prices. In Europe, with carbon pricing floating around $80 per tonne, the economic gap widens dramatically.

When you add in avoided infrastructure upgrades, carbon accounting compliance, and rising natural gas price volatility, the numbers start to look like an accountant’s dream. A 10 megawatt thermal system running at 8,000 full load hours per year can avoid 14,000 to 17,000 tonnes of CO₂ annually compared to a standard natural gas boiler, assuming an emissions factor of 56 kilograms of CO₂ per gigajoule. That’s the same as taking 3,000 to 4,000 cars off the road, and that’s just one installation.

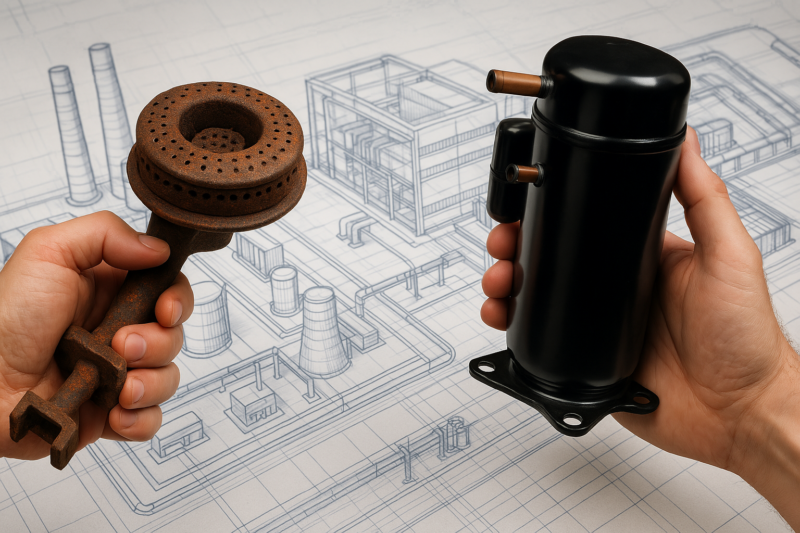

None of this is new technology. Conventional geothermal wells have been drilled for over a century. Industrial heat pumps have existed for decades, and the new generation can now deliver outputs as high as 160° Celsius and climbing, thanks to better refrigerants, oil-free compressors, and multi-stage designs. The difference today is that the use case is finally urgent enough — and the economics finally sharp enough — to matter. The rise in carbon prices, the fall in wind and solar LCOE, and the growing realization that process heat is the blind spot in many decarbonization plans are pushing this once-niche combo into the spotlight.

This isn’t some magical new technology stack. It’s plumbing and thermodynamics. It’s heat exchangers, compressors, and pumps. It’s basic, low risk directional drilling technologies from fracking. What’s changed is that it’s now cheaper to drill a 2-kilometer well than to keep importing fossil fuels forever.

Geothermal wells are expensive. A typical 2.5 kilometer doublet might cost between $8 and $12 million, depending on geology and local rig rates. Add another few million for the heat pump system, piping, and integration. But this isn’t a luxury purchase. It’s infrastructure that lasts 30 years with low operating costs and minimal inputs. The lifetime economics are favorable, especially when the alternative is locking yourself into a volatile gas market with increasing carbon liability.

Then there’s the risk — what if the well underperforms? That’s a fair concern, which is why risk mitigation tools like geothermal insurance pools and exploration grants exist in countries that take this seriously. Germany, France, and the Netherlands have all adopted such schemes to good effect.

The other supposed barrier is integration. How do you retrofit an existing steam loop to accept heat from a heat pump? Easy — you don’t. You connect the geothermal system to the feedwater preheater or use a secondary loop. Industries retrofit things all the time. New dryers, new chillers, new filtration lines. Integrating a high-efficiency heat pump that delivers hot water or steam at 120° to 160° is hardly exotic engineering.

What’s missing isn’t technology. It’s focus. Geothermal and heat pump integration is stuck in a liminal space between energy efficiency and renewables, and so far, it hasn’t fit neatly into policy buckets. Renewable energy support has mostly gone to electricity, while industrial energy policy remains fixated on hydrogen and biofuels. Neither are ideal fits. Green hydrogen is at least five times the cost of natural gas per unit of heat, and biomass, while useful, has scaling and logistics constraints, along with air pollution challenges.

Geothermal plus heat pumps offer a pathway to electrify process heat at scale without requiring gigawatts of new capacity overnight. The heat is dispatchable, the footprint is small, and the integration is technically straightforward. As a note, it doesn’t eliminate increases in electricity demand. We’re talking 5 MW industrial heat pumps. Even with coefficients of performance of four to ten, we’re still taking in the MW range of electricity for the 5 MW of heat. More electricity is still required, but it’s a more manageable amount.

Policy has often been the barrier, but that’s changing. In Kenya, the Olkaria geothermal complex is being expanded not just for power, but for direct industrial use. A special economic zone is being built next to the wells, offering firms access to both geothermal electricity and process heat. It is geothermal as industrial infrastructure, not just grid filler. In Europe, companies are exploring cluster models — shared geothermal loops feeding multiple factories in an industrial park. In Turkey, geothermal-heated facilities are drying agricultural products like figs and peppers.

China doesn’t yet have scaled moderate-depth geothermal + industrial heat pump systems for factories, but the components are there. They have more district heating geothermal than any other major geography and they are leaders in industrial heat pumps leveraging waste process heat. Policy and research support is growing. Pilot projects are likely to emerge this decade as part of the country’s push to decarbonize industrial heat.

Bent Flyvbjerg’s work on megaproject risks should be stapled to every industrial boardroom door — and the lessons for geothermal are clear: when you go deep, start fracking, or depending on first-of-a-kind tech, black swans start circling. Enhanced and ultra-deep geothermal? Those are textbook Flyvbjerg traps. You’re drilling 5 to 10 kilometers into uncertain formations, fracturing rock, managing microseismicity, and praying the reservoir holds pressure. Costs balloon, timelines stretch, and you’ve basically engineered a bespoke science project beneath your feet. The Icelandic Deep Drilling Project cost over $30 million and hit magma.

Now compare that to conventional geothermal at 1.5 to 3 kilometers, paired with industrial heat pumps. You’re dealing with known geology, established drilling techniques, and temperatures that don’t melt steel and fry normal drilling electronics. Your failure modes are boring — maybe the flow rate’s a bit low, maybe the pump needs a swap. That’s not a black swan. That’s Tuesday in plant maintenance. Heat pumps are factory-built, modular, and serviceable by the same HVAC contractor who installed your chiller. No fracturing. No exotic fluids. No seismic tail risk. In Flyvbjerg’s terms, this is reference-class, risk-contained, and scalable. One is an infrastructure asset. The other is a science fair in a mine shaft.

Geothermal plus industrial heat pumps won’t be the headline act in any decarbonization strategy. They’re not flashy. They don’t glow blue, require platinum catalysts or extend the life of the fossil fuel industry with greenwashing. But they do one thing extremely well: provide high-efficiency, low-carbon heat at scale, around the clock, with no combustion and no seasonal dips. Like most of the real climate solutions, they’re boring. In a world where industry is running out of excuses to keep burning things, boring is good.

The future of a lot of industrial heat won’t arrive with a bang. It’ll arrive with a quiet hiss of high-pressure refrigerant and a thousand wells slowly turning the earth’s ambient warmth into clean process energy. No drama or fuss. Just a shift in how we think about heat: not as a problem to be solved with magic gases or nuclear pipe dreams, but as a system to be designed, optimized, and scaled using the physics and tools we already have.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy