Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Last Updated on: 23rd March 2025, 01:39 pm

When the forecast called for a hot summer day, my old Irish grandmother would deploy the striped canvas awnings over her windows and pull down all the window shades. It might seem counter-intuitive, but blocking the sunlight did keep temperatures inside the house fairly comfortable. It was a primitive form of geoengineering. Stardust is an Israeli startup that has proposed to doing the same thing but on a far grander scale.

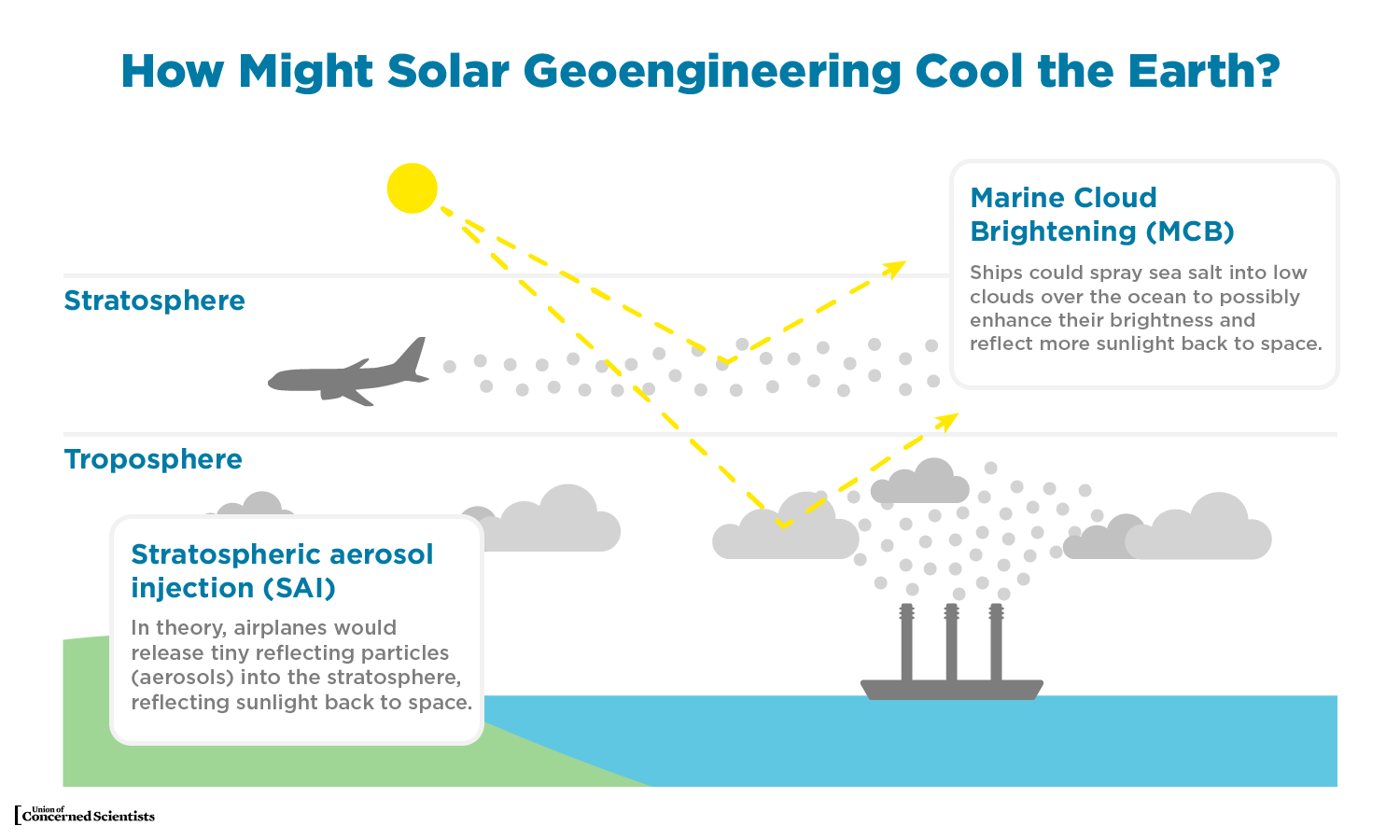

According to Wired, Stardust is developing proprietary geoengineering technology that would help block the sun’s rays from reaching the Earth. The theory is that the Earth would be cooled somewhat by the new technology, just as the awnings and window shades kept my grandmother’s house cooler. Stardust was formed in 2023 and is based in Israel but incorporated in the United States.

Most geoengineering research today is being led by scientists in the US at universities and federal agencies, which means the work they are doing is open to public scrutiny. As a private company, Stardust is driving the development and possible deployment of technologies that experts say could have profound consequences for the Earth in a way that is largely obscured from public scrutiny. That is setting off alarms in the scientific community, because if a geoengineering project goes awry, it could have a dramatic or even a catastrophic effect on weather patterns. For instance, the monsoons in South and East Asia could be altered, making those areas and the two billion people who live there susceptible to much wetter or drier conditions than they are used to.

Geoengineering For Fun & Profit

Few outsiders know anything about Stardust or its plans. The company has not released details about its technology, its business model, or exactly who works for it. So far as anyone can tell, Stardust is planning to develop and sell proprietary geoengineering technology to governments that are considering making modifications to the global climate. In other words, it is acting like a defense contractor for climate alteration. This is uncharted territory with few national or international rules and limited oversight. A recent report by the company’s former climate governance consultant, Janos Pasztor, called for the company to “be as transparent as possible, be available proactively to respond to questions people may have, and also to engage with other actors,” but that call has gone largely unheeded by Stardust.

Stardust CEO and co-founder Yanai Yedvab is a former deputy chief scientist at the Israel Atomic Energy Commission, which oversees that country’s clandestine nuclear program. In a post on Undark, Yedvab wrote: “Stardust is a startup focused on researching and developing technologies that may potentially stop global warming in the short term.” He added that the company is “studying and developing safe, responsible, and controllable solar radiation modification” and has a goal of enabling “informed and responsible decision making of the international community and governments.”

Despite Stardust’s low profile, the company rejects being referred to as “secretive.” “Publishing all the products of our research without any exception is critical,” Yedvab wrote, adding that the company is “unwaveringly committed” to publishing results “as one of the measures to gain public trust.” Stardust has not published any of its research at this time, but Yedvab stressed it will do so once “scientific validation is concluded” on all of its results. Such statements may or may not be reassuring. Scientists have done extensive studies of the effects of sulfates injected high into the atmosphere by volcanoes. “We know that sulfuric acid air pollution causes mortality, and we roughly know how much. There’s more than a century of studies. We’re very unlikely to be wrong about that,” said David Keith, head of the Climate Systems Engineering initiative at the University of Chicago and an advocate of geoengineering research.

The Least Worst Alternative

In a new study, Keith and his colleagues argue the health risks of sulfate particulates in the atmosphere are far less than the existential risk of doing nothing about our overheating planet. Stardust will use a proprietary aerosol particle whose effects on the atmosphere are less well understood, according to Keith. The company plans to distribute the particles through a machine mounted on an aircraft. According to Pasztor’s report, which he published on LinkedIn last September, the company is engineering the particle and a prototype of the aircraft mount while it is developing a system for modeling and monitoring the climatic effects. Over the coming year, the company is planning to advance those technologies and testing those particles in the stratosphere.

Yedvab confirmed that they are working on the technology, saying in a statement to Undark that any such experiment would be done in a “contained, non-dispersive manner,” meaning that its particles would not be strewn over a wide area. It also committed to publishing information about any such outdoor geoengineering tests. Yedvab said that the company has not performed any such outdoor experiments yet, but it has done “a few outdoor aerial checks.” That means they have tested their dispersal system “under flight conditions,” but they haven’t yet scattered their aerosols in the atmosphere.

Those experimental particles do not appear to involve sulfates, meaning there is little data showing how well they might work. “It might be better in some respects, but on the other hand it’s going to be much harder to be confident about knowing what its risks are,” Keith said. The statement by Yedvab confirmed the company is testing non-sulfate particles. “The ability to tailor particle properties to meet a broad set of requirements — safety, effectiveness, cost, and dispersibility — is a key advantage of our approach, giving it a distinct edge over sulfates and other candidate particles.”

No Rules

Right now, there are no international rules or treaties that put obvious limits on this kind of work. As a result, an individual company or government can take dramatic gambles with the climate in ways that could affect billions of lives, and it doesn’t have to get permission from anyone to do it.

According to Pasztor, there should be rules that allow more people to be involved in that decision before it happens. Failing that, he said, Stardust should voluntarily tell the public what it’s doing and make sure it’s getting input from lots of different groups of people before it tinkers with the planetary thermostat. “There’s one big area, transparency and outreach, to engage with the rest of the world, to the extent that the IP process allows,” he told Undark. Building trust through “a strategy of maximum transparency” should become a priority for them, he recommended in the report.

The Center for International Environmental Law is concerned that what Stardust is doing could violate the Convention on Biological Diversity — a de facto moratorium on geoengineering activities. “By developing and planning to commercialize solar geoengineering technology, Stardust is accelerating a reckless race and potentially violating agreements of the Convention on Biological Diversity,” said CIEL’s geoengineering campaign manager, Mary Church, in February. Any deployment of the technology would likely “be controlled by a handful of major powers and corporations,” she said.

As nations consider geoengineering, Stardust could be poised to sell them tools to meet those goals, several experts said. In an emailed answer to questions about its business model, Yedvab described the company’s approach as “founded on the premise” that solar geoengineering “will play a critical role in addressing global warming in the coming decades.” Its portfolio of technologies, Yedvab added, “could be deployed following decisions by the US government and international community.” Well, that is a comforting thought. Now a certain US president could use this technology as a weapon to punish any countries that refuse to knuckle under to his demands.

“We anticipate that as US-led [geoengineering] research and development programs advance, the value of Stardust’s technological portfolio will grow accordingly,” Yedvab wrote. Pasztor’s report adds that if governments decide not to pursue geoengineering, investors “risk not receiving a return on their investment.” Oh, the horror! Nothing must be allowed to interfere with an increase in shareholder value. Pasztor argues that Stardust is “operating in a vacuum, in the sense that there is no social license to do what they are trying to do.”

A Dangerous Distraction

Benjamin Day of Friends of the Earth, an environmental group that has long dismissed geoengineering as a “dangerous distraction,” said, “I don’t think it’s compatible to have venture capital funding and to be committed to scientific ideals.” The problem, he said, is that Stardust engineers have a vested interest in finding that stratospheric geoengineering can and should be done. “There’s no private market for geoengineering technologies. They’re only going to make money if it’s deployed by governments, and at that point they’re kind of trying to hold governments hostage with technology patents.” Stardust has received an estimated $15 million in venture capital funding, primarily from Awz Ventures, a Canadian-Israeli venture capital firm, in addition to a small investment from SolarEdge, an Israeli energy company. Neither company responded to Undark’s requests for comment.

Stardust said that it receives no funding from the Israeli Defense Ministry and made clear to Pasztor that it has no connection to the Israeli government. However, Awz’s partners and strategic advisers have strong ties to Israeli military and intelligence agencies, including former senior directors of agencies like the Mossad, Shin Bet, and Unit 8200.

Defense scholars and security experts don’t see geoengineering technology as a potential weapon, but they do view it as something that could disrupt international relations, according to Duncan McLaren, a researcher with the Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal at American University. McLaren suspects the company is following a standard procurement model of the defense industry, where governments get military technology from a few monopolistic companies like Boeing and Lockheed Martin that develop it mostly in secret. “That tends to be a space in which public involvement in decisions is utterly sidelined,” McLaren said, and there is “the potential for this to be a highly undemocratic process of moving us down a slippery slope to solar geoengineering.” If humanity needed this technology, he added, “I definitely want it to be controlled democratically.”

The Takeaway

Geoengineering is a tool. Like any tool, it can be used for good or evil. From one perspective, it is yet another in a long line of distractions by the fossil fuel industry — like carbon capture — to allow it to continue doing business as usual while the Earth roasts. “Don’t worry about all the carbon dioxide and methane pollution we are pumping into the atmosphere every second of every day. We are making too much money to stop and besides there is this magic technology called geoengineering that will save us from ourselves at the last possible moment.”

From another perspective, humans have proven time and time again they are incapable of living a sustainable lifestyle, so we will need geoengineering to pull our chestnuts out of the fire right when human activity makes living on Earth no longer sustainable. I don’t know about you, but the idea of a private, for-profit company selling geoengineering technology to the highest bidder will not help me sleep more soundly at night. This company is deeply embedded in the defense and security industry in Israel and the US. That is hardly a comforting thought.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy